You can listen to the audiobook of The Outlaws of Maroon, read by Tiana Melvina, HERE

You can read and download the novel as a pdf HERE: The_Outlaws_of_Maroon

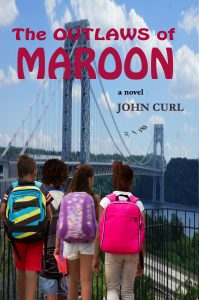

The Outlaws of Maroon is an adult novel about the world of children. In McCarthy-era New York City, fourth graders find a forgotten room in the foundations of a building, where they struggle to live their dreams. As the cold war of 1950s America envelops their school, they become radicalized.

“A well-crafted tale with a retro style.” — Kirkus Review

Many thanks to filmmaker Jai Jai Noire for producing the video, and Dan Fedoranko for the short readings from the book. The full audiobook is now available, read by Tiana Woods.

My new novel, The Outlaws of Maroon, is about a group of kids rebelling in a New York City public school during the McCarthy era of the 1950s. It’s about the world of children and the adult world in conflict, in an atmosphere of political repression and attacks on freedom of thought. Much of the story takes place in the Little Woods, a fenced-off abandoned lot not far from the school. It’s a wild wooded area bordering the West Side highway in upper Manhattan, supposedly inaccessible and off limits. The Outlaws of Maroon is not a kids’ book. It’s an adult novel written to also be accessible to younger people. The narrative begins from the kids’ point of view, then expands and becomes more complex as they increasingly come into conflict with the adult world. Gabe and Henry are both from working class families, living on the fringes of a gentrifying Washington Heights neighborhood. They’re both outsiders who feel oppressed by the city and by their school, and threatened by bullies. They find a forgotten room in the foundations of a building, and take it over as a hideout. Meanwhile the Little Woods is threatened by developers and their school’s in turmoil because the vice-principal has convinced herself that the school has been taken over by subversives and she’s determined to root them out. To defend themselves, Gabe and Henry bring other kids from their class down to the hideout, including two girls, Ari and Elkie. All of them are in difficult home situations. As the cold war envelops their school, they form a group that is somewhere between a club and a gang, and organize themselves for mutual support against an adult world that has failed them. In the Little Woods and the hideout, they construct their own world, and struggle to live their dreams. But a chain of events leads them to clash with their school, with the developers, and with government agents. The result is kids’ ingenuity pitted against overwhelming force. The Outlaws of Maroon tells a story about children organizing themselves when left to their own devices, banding together for support, learning to work together under difficult conditions and using their collective ingenuity to succeed. It’s also a tale about the end of childhood and the coming of consciousness. As to the title, as to what Maroon is, or where Maroon is, I hope you’ll read the book.

Here are audios of three brief sections , read by Dan Fedoranko.

Below you can read Chapter One.

THE OUTLAWS OF MAROON

CHAPTER ONE

Gabe and Henry set out the food near the garbage cans. Henry knew where all the strays lived. The cats, always on the watch for danger, crept cautiously out of the shadows when they saw him. The most skittish ones peeked from the alleys until the boys retreated far enough away, then darted out and scarfed it all down. Henry fed the neighborhood strays a couple of times a week, with kibble from a lady in his building, and Gabe often went around with him. Gabe hated fourth grade, and so did Henry.

After school and on weekends they hung out in the little park, Bennett Park, usually down at the far end by the granite rock, where the bushes and weeds were thicker. But some kids from Broadway started coming around and bothering everybody, so instead they started hanging out in the big park, Fort Tryon Park, which was further away, but had isolated corners and nooks to hide in.

Then they discovered the Little Woods. That’s what Gabe and Henry called it. It didn’t really have a name. People in the neighborhood sometimes called it that empty lot. Some said it was part of Fort Tryon Park, even though you couldn’t get there by any of the paths, and it was separated from the big park by a high chain-link fence. Other people said that Mother Cabrini’s Church owned the lot, even though Cabrini Boulevard separated it from the main church grounds.

The Little Woods started a ways up from Columbus School, across the street, beyond the last apartment building. Very few cars drove this way, because the street led only to the park entrance; and few people walked this way because of its isolation: it felt a bit dangerous. At the outer edge of the sidewalk was a black iron fence, and beyond that a sheer drop, over twenty feet down in some places. When you looked down, you could see the granite retaining wall holding up the edge of the sidewalk. At the bottom of the wall, a steep hill thick with trees and bushes tumbled down to a meadow at the West Side Highway. Closed off at the south end by apartment buildings, at the north by the park, on the east by the wall, and on the west by the highway, the Little Woods was almost inaccessible, a wild space right in Manhattan. That’s the way it was back in 1951.

Gabe and Henry found two ways to get down into the Little Woods. The short way was straight down, at a spot they called The Place, where a star maple tree grew close to the wall. Here they jumped the cast iron fence at the outer edge of the sidewalk, and lowered themselves down between the tree and the granite rocks, holding onto the branches, climbing down rock to rock. That was the shortcut from school. The long way was through Fort Tryon Park, which was pretty roundabout, but safer in terms of not being seen. Beyond the neat lawns and beds of flowers, winding macadam paths and old people on benches, under some bushes and dense undergrowth, the hooks that held the chain-link wires onto the metal post at the bottom were broken, and they pushed it aside enough to crawl under.

Now that spring was here, almost every day as soon as school let out, and on weekends, Gabe and Henry would slip down the wall and run around in the Little Woods. They didn’t have a lot of time on school days, because they had to be home by 5:30 at the very latest. None of the other kids ever went there or even knew that they went there. The teachers all said it was forbidden.

Once they were down there, nobody could see them, and they could run like crazy through the trees. Lots of birds and wild animals lived there. Squirrels and chipmunks and salamanders and sometimes raccoons or possums. Blue jays, red-tailed hawks, even an occasional hummingbird, and a couple of times at dusk they saw a big snowy owl. Once they watched a groundhog, with little oval ears and a round flat tail, sitting on a branch eating green unripe wild cherries. Occasionally they smelled a skunk. Henry saw a coyote there once, but Gabe didn’t see it. They got down on their hands and knees and howled like coyotes, but no real coyotes ever answered them. A few stray cats lived there too. Down towards the highway, the Little Woods leveled off into the meadow where a rainbow of butterflies—tiger swallowtails, mourning cloaks, painted ladies and numerous others—flitted from flower to flower, along with bumble bees and honey bees and dragon flies, and an uncountable number of other insects. In the middle of the meadow, at a distance from other trees, stood a majestic elm.

They would stretch out on Bear Rock, and talk and talk, overlooking the Hudson River and the bridge, gazing across at the cliffs and beyond that toward Maroon hidden from view somewhere past the line of trees.

At twilight, the lightning bugs came out in the meadow, and sometimes Gabe and Henry ran around catching them in nets they’d made from old pillow cases and wire clothes hangers. They put the fireflies into jars to make lanterns, used them to light their way along the paths, then always let them fly away free.

All spring Gabe had been telling Henry about Maroon and showing him pictures. Henry wanted to hear about it over and over. He was coming to Maroon with Gabe for two whole weeks in July, during summer vacation. They couldn’t wait. Every day felt like forever, school was never going to end.

Maroon was just seven acres, but behind the old chicken coop was the stream and the pine forest, and to Gabe it was a whole vast world. Almost every day he met up with the local farm kids, who had chores in the morning but could usually roam unconstrained until dusk, when the crickets started singing and the whippoorwills began to call. Mom grew up there in New Jersey a long time ago, back before the Great Depression when Grampa was trying to be a farmer. Grampa still lived part of every year there, and the whole family went there every summer from as far back as Gabe could remember. Well, Dad still had to work at his job in the city, but he came out for one whole week and on weekends.

The little clapboard house had only three small rooms, but to Gabe it was perfect, or almost perfect. They got their water from an outdoor hand pump, used kerosene lanterns for light, had an old ice box instead of a refrigerator, and an outhouse which Gabe didn’t much like. Beyond in back was the old chicken coop, now a storage shed, and beyond that the pine forest, the wild huckleberry bushes, the gurgling brook, the little pond with frogs and water skeeters. Down the road was the secret swimming hole on Metedeconk Creek. In the forest you almost never saw the bigger animals, but you heard them rustling, and sometimes caught a glimpse of one through the underbrush, or saw their paw or hoof prints.

When people asked why they called the old farm Maroon, even though the house was yellow and the roof was red, Grampa Benjo always explained that it wasn’t maroon the color, but maroon like when your boat hits a rock in the middle of the ocean and you’re marooned on an island. It didn’t make a lot of sense to Gabe, but Grampa didn’t exactly understand some words, since English wasn’t his first language.

Because of Maroon, Gabe knew both country and city, but Henry had lived his whole life in the big city. He had never been to the country, or even away to summer camp. Gabe tried to describe to him what country life was like, but could never quite explain it, just like he couldn’t quite explain to the farm kids what city life was like. But Henry still knew an awful lot about birds and animals and bugs, usually even more than Gabe, but he got it from hanging out in the parks and from books.

Washington Heights was a pretty diverse neighbor-hood. You could hear many accents and languages on the street. Almost all of the kids in Columbus School belonged to one ethnic group or another. But each group mostly hung out by itself, and Gabe didn’t quite fit into any of them, and neither did Henry. In class, Henry usually spoke with his school voice, but outside, or when he was worked up about something, he spoke more like his family, but the teachers always corrected you when you spoke that way in class. When anybody asked Henry what he was, he never really answered. He was sensitive about it. Henry’s mom and gramma and the man he called Pimple Simon all looked different from him. Gabe never saw Henry’s dad. It didn’t really matter to him. Gabe’s own family was pretty mixed too, and he was sensitive about it too. When he started kindergarten a long time ago, Mom said, “If they ask what you are, tell them you’re an American.”

For Gabe, summer in Maroon meant feeling happy and free. In contrast, winter in Manhattan was bleak, and meant being constricted and confined. Whenever he looked out through his bedroom window, tucked up alongside the George Washington Bridge, he imagined Maroon out there, across the river, waiting for him.

The sidewalk was filled with kids funneling in from the surrounding blocks. Every morning they gathered outside the gate in front of Columbus School, and waited until the second bell rang and the doors opened.

Today was assembly day, and everybody had on their assembly outfit. The boys wore white shirts and blue ties, and the girls wore white middy blouses with gold scarves. Blue and gold were the school colors. At ten o’clock the whole school would be marching down to the auditorium.

That morning, as soon as he got out of the house, Gabe pulled off his tie and stuck it in his pocket. Gabe hated wearing a tie. It made him feel like a dog on a leash. Henry hated ties too. Gabe’s mom always remembered when it was assembly day, and made sure that he was dressed properly.

Gabe saw Henry coming toward him in the crowd, in his green corduroy pants a couple sizes too big, worn in the knees, suspenders, and his sky blue cap with a little hummingbird embroidered on it. Not only did Henry have no tie, but he was wearing his flannel shirt with red, white and black cross stripes, kind of frayed in the elbows. He was a little shorter than Gabe, more wiry. His ears stuck out of a shock of brown kinky hair that Gabe’s mom always said needed cutting.

When Gabe saw Henry, he remembered his tie, stuck his hand in his pocket, but it wasn’t there.

Henry whispered, “After you left yesterday, I found something amazing.”

“What?”

“This is top secret. You won’t snitch about this ever, right?” Henry looked him in the eye.

“I’m in on this. I won’t tell.”

“I’ll show you after school.”

“Show me now.”

“It’s not here. It’s down in the Little Woods.”

When they finally got to class, they separated, each to his seat. Miss Odelia had seated them on opposite sides of the room.

Miss Odelia began, “Today as you know is assembly day. I’m very pleased to see that almost everyone has remembered to wear your assembly outfits. Everyone except for Gabriel and Henry. Would you two please come up here.”

They slunk up to the front.

She opened a desk drawer and pulled out a white shirt and two bow ties, the baby kind you clip onto your collar with a metal snap. “Put these on.”

No matter how much Gabe hated ties, clip-on bow ties were the worst of the worst.

She handed him a bow tie, and Gabe scuttled back to his seat.

Henry stood there looking up at her.

Miss Odelia said, “Take off that shirt.”

“Here?” Henry asked.

“Right here.” She was trying to humiliate him in front of the class.

A nervous giggle circled around the room.

Henry unbuttoned his flannel shirt while the class tittered. He pulled it out from under his suspenders, and let it fall to the floor. His sleeveless undershirt had holes. Miss Odelia shoved the white shirt at him. He grasped it reluctantly.

“Put it on.”

Gabe could see that Henry now had the problem of putting on the white shirt without taking off his suspenders, which were holding his corduroy pants up. He started but got self-conscious and couldn’t quite figure it out, so he just put it on over his suspenders. It was several sizes too big and looked ridiculous on him.

“Don’t leave it hanging out,” Miss Odelia said. “Tuck it in.”

He couldn’t tuck it in without unhooking his suspenders. Henry got flustered, and just stood there, looking pained. The giggling died out. Most of the kids felt sorry for him, realizing that they could be next. Except for Jim Stoloff, who had an oily grin on his face, and so did Rory Golman, they were loving it.

“Go into the clothes closet,” Miss Odelia finally muttered. “Here, take the tie. And pick up your shirt from the floor.”

Henry slunk off and disappeared into the closet, which was on one side of the room, with sliding doors.

“Now, has everybody done your assignment?” Miss Odelia asked. “Has everybody memorized the words to the fourth stanza of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’?”

A few voices in unison, “Yes, Miss Odelia,” while the rest of the class mumbled nonsense syllables.

“Now, today at assembly,” Miss Odelia went on, “we are going to be singing the fourth stanza of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ for the first time. I hope you are all prepared, I hope you all did your homework and now you have the last stanza memorized as well as the first stanza. I gave you this assignment last Friday, so you had ample time to do it, and I have reminded you several times since then.”

“Yes, Miss Odelia.”

Henry emerged from the closet, the shirt tucked into his pants under his suspenders, and the bow tie in place. Gabe saw the defiance in Henry’s eyes.

“Did anyone not do their homework?” Miss Odelia gazed around the room.

Roco raised his hand.

“Francisco, you didn’t do your homework?”

The teachers called him Francisco, but the kids called him Roco.

“My cousin was having a baby.”

“You gave that same excuse last month.”

“That was a different cousin.”

“You shouldn’t let that stop you from doing your homework. You’ll need to catch up.”

“She didn’t have one hair, the baby, not my cousin, she looked like a egg, and it was soft on top, like you could stick your finger right into her brain. I’m not kidding.”

The class tittered. Miss Odelia ignored it.

“Anyone else not do your homework? Excellent. Then everybody else has studied the words to the last verse of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at home, and has come prepared with questions about anything you didn’t understand.”

She stepped toward the large poster pinned to the board, with a bald eagle scowling at the top, above all four verses.

“So what are your questions?” She scanned the room. “No one? Surely someone must have a question. Everybody understands every single word in the song? Arisu.”

Ari said, “What’s a hireling?” She was slight, one of the smaller girls in the class, but knew how to use her tongue.

“Let’s look at those lines. They’re in the third stanza.” She stood at the board with her pointer. “Please read that line out loud.”

Ari read, “No refuge could save the hireling and slave.”

“Does anybody know what a hireling is?” No one raised their hand. She went on, “A hireling is a soldier who fights for money. Another word for that is mercenary.” She wrote both words on the blackboard. “In the American Revolution, there were mercenaries fighting. Which side were they fighting on, Arisu?”

“The British?” she answered uncertainly.

“That’s right. German mercenaries, called Hessians, were fighting with the British, trying to stop the Americans from gaining our freedom. Does that answer your question, Arisu?”

“What about the slaves?” Ari replied. “What were the slaves doing there?”

“Oh yes,” Miss Odelia said. “Well, those were still the days of slavery, before the Civil War.”

“Who were the slaves fighting for, the Americans or the British?”

A puzzled expression came over Miss Odelia’s face. She gazed at the words on the poster as if she had never actually thought about it until now.

Then she said hurriedly, “That’s in the third stanza, and we don’t have time today for a full discussion of all four verses. Today, we’re focusing on the fourth verse, because that’s the one we’ll all be singing today in assembly. Does anyone have any questions about the last verse? How about you, Henry?”

He just shook his head.

She gazed right at Gabe. “Gabriel, did you do your homework?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have a question?”

Two days before, Gabe had been studying at his little table, when Grampa Benjo came in, yawned and stretched his arms wide. “What a day!” “Grampa, I’m trying to read.” “Sorry for breathing. Stop burying your nose in those books once in a while, run around the block a few times. It’ll do you good.” “I’m doing my homework. I’ve got to get it done.” When he needed help with homework, Mom usually helped with arithmetic and Dad with writing. Once in a while he asked Benjo, but he usually wasn’t much help, and often left Gabe more confused, so he just asked him when nobody else was available. Benjo came around and looked over his shoulder. “What’s that?” “It’s The Star-Spangled Banner. I’ve got to read it for school.” “Oh, say can you see…” Benjo began to sing, then trailed off. Gabe said, “That’s not even the right melody.” Benjo stared at the page. “Look at this: Then conquer we must. That’s what the politicians always say: then conquer we must. Why? Why do we always got to conquer?”

So when Miss Odelia asked Gabe if he had done his homework and if he had a question, first he drew a blank, and then he found himself saying, “Why do we always got to conquer?”

“Read the line to us.”

“Where it says, Then conquer we must.”

“Yes, that is in the fourth stanza, the one we have been memorizing. That line goes together with the next one. The whole thought is, Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just. Does that answer your question?”

“It still doesn’t make sense to me.”

“What part of it doesn’t make sense to you?”

“What’s our cause? And what does that mean, when it is just? When it’s just what?”

Jack raised his hand. “When it’s just a joke?”

“Kelly.”

“When it’s just an excuse.” Kelly had thick glasses and was left handed. He was notorious back in second grade for being on TV on Howdy Doody in the Peanut Galley, and getting kicked out by Buffalo Bob.

Miss Odelia flashed a tense grin and glanced around the room. “What is a cause? What is a just cause? What does that mean? Elkie?”

Elkie replied, “Just is like justice. Because of justice.” Elkie had come into their class a few weeks after school started last fall. She must have been new in the neighborhood. Her clothes were somewhat different from the other girls, and she pronounced some words with an accent, just certain words.

“Good answer. Very good, Elkie. Because of justice. We must conquer because of justice. Does that answer your question, Gabriel?”

“Kind of. I’m not sure. I’ve got to think about it.”

Henry’s hand shot up. Miss Odelia reluctantly called on him again.

“How do we know?”

“How do we know what?”

“How do we know when our cause it is just?”

Miss Odelia set her jaw. “America’s cause—our cause—is justice. Americans believe in justice. Don’t you, Henry?”

Henry said, “What is justice?”

She glared at him. “That’s more than we have time to get into today.”

The bell rang twice. The speaker above the door crackled and Miss M. Drannily’s voice echoed through it. “Time for assembly.”

“I’m afraid we don’t have any more class time this morning.” Miss Odelia sighed. “Everyone line up in size place with a partner, boys with boys and girls with girls.”

In the midst of the shuffle, Gabe and Henry met at that back of the room.

Henry said, in a low voice, “That’s it. I had it.”

“What do you mean?”

“They want to break us like ponies, ride around on our backs. Not me. I’m not taking this junk any more. I’m out of here. I’m quitting this stupid school.”

“Where are you going to go?”

“To Maroon.”

“But that’s just for two weeks.”

“I’m sure not coming back here to this junk. No way. I’m not coming back. I’m not living in this jail my whole life, that’s for sure. I’m breaking out. Want to break out? Want to stay in Maroon with me?”

Before Gabe could answer, the line started to move out the door. They scrambled to find their size places.

Gabe wound up with Jim Stoloff as his partner, and Henry wound up right in front of Rory Golman. Jim poked Gabe in the back.

Gabe turned. “Don’t do that.”

“Do what?”

“You know what you did.”

“Nobody touched you.”

Miss Odelia said, “Is something wrong, Gabe?”

“No, nothing’s wrong.”

For some reason they both hated Gabe and Henry. They lived in Monarch Towers, a group of tall buildings set off from the rest of the neighborhood by fences and guards, with clipped rolling lawns and patches of multi-colored flowers in neat rows, that seemed to be always in bloom. Gabe had to walk past there every day on his way to school, and he always crossed the street when he saw Jim and Rory and Jim’s big brother. Monarch Towers had an elaborate kids’ play area with monkey bars and slides and tunnels and see-saws, but only kids who lived there could use it, and it was usually empty, because only a few kids lived there. Gabe and Henry snuck in a few times, but the gardener chased them out. Once they tried to slip into the building through the delivery entrance, to see what was inside, but the doorman grabbed them. The super recognized Henry because Pimple Simon—Henry’s gramma’s husband—was a super too, and Pimple Simon hit Henry for it, and said he would hang him in the closet if he ever did it again.

All the classes marched through the hall, down the stairs to the auditorium, a big theater with a stage in front, a flag, an upright piano, and a podium. On the stage were Principal Hopper and the Drannily sisters. While they entered the auditorium, the junior sister—Miss C. Drannily—played her usual marching music on the piano. Each class filed into a different section, and each kid stood in front of a seat. They had to wait to sit down until the senior sister—Miss M. Drannily—told them to. Mrs Hopper, with her big bush of blue-white hair, was planted next to the flag on the stage, and Miss M. Drannily stood at attention by her side.

Together the Drannily sisters taught the upper grades Language Arts, which consisted of Miss M. focusing on grammar and Miss C. teaching composition and literature. In those days Columbus School was kindergarten to sixth grade. The lower grades stayed with their homeroom teachers all day, except for lunch and recess, while the fifth and sixth graders had special teachers for different subjects. Miss M. looked a little older than Miss C. They wore similar long brown dresses but M. kept her hair pulled back into a bun, while C. wore hers down. M.’s tiny waist was cinched by a black belt, and C.’s by a pink one. Miss M. doubled as the vice principal and school disciplinarian, and was always mad about something. Miss C. taught art and music appreciation, and was the school librarian. The kids mostly liked Miss C. She always had a pained smile in her eyes. Nobody in the school ever called her Miss Drannily, because Miss Drannily always meant her sister, Miss M. Sometimes Gabe saw the Drannily sisters striding in and out of Monarch Towers, so he figured they must live there.

As always, when everyone was settled and seated, Principal Hopper shuffled to the podium, told everybody to face the flag, place your right hand over your heart, and recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

Then Miss M. Drannily took center stage, her back ramrod straight, and declaimed, “From now on in every assembly we will be singing both the first and last verses of our national anthem. Today is the first time. I assume everyone is prepared.” She raised her hands like an orchestra conductor.

Miss C. struck a chord on the piano and began playing, Miss M. started waving her hands and singing, the kids joined in. It actually sounded pretty good.

Then Mrs Hopper said, as always, “I will now read the Twenty-third Psalm.” Gabe knew the psalm by heart, from having heard it so many times. Mrs Hopper must have had it memorized too, but still always read from the open Bible on the podium, which she probably just used as a prop.

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…” She began to hack and covered her mouth with her embroidered hanky. Her cough had gotten worse as the school year progressed, and she had begun to lisp and stammer. “Ththurely…” She screwed up her face and moved her jaw from side to side, then tried again, “Surely goodness and mercy ththall…” It turned into a wheeze, almost a whistle. It was like she was losing control of her jaw or her tongue. With a determined expression, she continued, “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the houth of the Lord for ever. Amen.” Mrs Hopper hacked a few more times, shut the Bible, stepped back from the podium, shuffled over to Miss M., whispered something through her handkerchief, then dropped into a folding chair next to the flag, Bible in her lap, looking somewhat crestfallen.

Miss M. said, “Mrs Hopper is not feeling well today, and asked me to give the talk that she planned.” Drannily cleared her throat. “Those who have been in my grammar class know that I always assign a word of the day. Every day, never miss a day. That way we grow our vocabulary, one word at a time. Today’s word is vigilance, v-i-g-i-l-a-n-c-e, vigilance. This afternoon when you go back to your homeroom, every class will have a discussion on vigilance. Does anybody know what that word means? Hands?”

A couple of hands shot up and a few others tentatively raised. Drannily, as was her practice, didn’t call on anybody but answered herself in her high-strung tone, “Vigilance means being always watchful, alert, wary, keeping a careful eye out for danger. It comes from the Latin vigilare, to keep awake. Sometime this afternoon—and I won’t say when—Columbus School will have a duck-and-cover drill, so we will all be vigilant and prepared for the nuclear threat that all Americans are concerned about. And we must also be vigilant and prepared for another threat, one perhaps even more alarming because it is insidious, like a snake in the grass. The very foundations of our freedom and democracy, the envy of the world, are under threat from enemies right here in America, un-American calumniators who hate freedom and democracy, and want to take them away from us. These are new and different enemies, perhaps even more treacherous because many of them may look just like ordinary people in our neighborhood. But we do not need to be afraid: we need to be alert, vigilant. We can all help catch them. This afternoon, third graders and up will receive a special VIP Vigilance note pad and pocket pencil, which we call V-Pads. Your homeroom teacher will explain all the details, what entries are appropriate, and what are not. Columbus School is honored to be selected for this pilot program. Do the work carefully, because in one week all the pads will be collected and handed in to our friends at the Internal Protection Agency. So who is going to be vigilant? Hands?”

Again, several of the same hands shot up. Miss M. ignored them and continued, “We all are. Each of us. It’s up to all of us. We keep our eyes open, our ears peeled. Vigilance! V-i-g-i-l-a-n-c-e! Vigilance!”

Her sister Miss C. punched some chords on the piano, they led the kids in singing ‘O Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean’ and few more songs, then marched everybody back to their homerooms.

To continue to Chapter Two, please open the pdf file HERE, or acquire the print book, the ebook, or the audiobook.

0 Comments